A conversation about Kuti with Tommi Musturi, co-founder and member of the KutiKuti collective. Written by Saskia Gullstrand.

There’s nothing like Kuti in Sweden.

Kuti is a Finnish tabloid-style comics anthology run by the KutiKuti collective. It looks like a broadsheet newspaper, but every page is crammed with comics, illustrations, and hand-drawn advertisements. Both the physical magazine and the online PDF version are free for anyone to take and read. Kuti is home to contemporary comics and art comics and is distributed all over Finland and abroad. It has had an immense influence in shaping Finnish alternative comics over the last ten years.

The comic scenes of Finland and Sweden overlap in several ways. Artists from both countries are being translated and published in each other’s country, as well as participating in festivals and living and working in both countries. This collaboration, which relies greatly on personal connections and relationships between artists and people active in the respective communities, is well-developed and growing. Since the comics scenes in both countries are so small, any one artist can easily diversify the community just by doing something different from those who came before. Yet the traditions of contemporary comics look very different in Sweden and Finland and this is visible in the stories and styles coming out of each country.

Let’s just put it this way: there’s nothing like Kuti in Sweden.

Cover of Kuti #11

One quick and easy way to see the differences between independent comics in Finland and Sweden is to compare Kuti to the Galago anthology. Galago has a similar role in Sweden as Kuti has in Finland, seeing as it is the largest magazine for alternative comics in Sweden over the past decade. But the content of these two magazines is remarkably different. A Swedish comics artist might look at Kuti and be struck by the rainbow splatter of colourful and experimental storytelling that is not aiming to please anybody. A Finnish artist might turn to Galago and discover volume after volume of autobiographical stories, contemporary realism and political satire. The terms of production also differ, with since the publisher of Kuti is the non-profit KutiKuti collective, while Galago is released by the commercial, independent publisher Galago/Ordfront. Galago can afford to pay the contributors for their participation and connect readers to their work as subscribers, while Kuti is free for everyone, online and as paper copy. Even though neither the Finnish nor the Swedish alternative comics scenes can be reduced to Kuti or Galago, the magazines are evidence of how different aesthetics, styles and conditions for printed alternative comics have blossomed in Sweden and Finland.

So, there’s nothing like Kuti in Sweden. What’s the deal with Kuti then? To understand the history and current state of this institution of Finnish contemporary comics, I asked Tommi Musturi for an interview. Tommi is co-founder and member of the KutiKuti collective. He knows the history of Finnish alternative comics from personal experience, since he has been part of the scene through the 1980s, 1990s and the millennium years. He is at the heart of today’s Finnish comics and has been throughout all those years: drawing his own stories, making art, organising and publishing.

In September 2016, we sat down at a table in a Helsinki café with some cake and wine, to talk about the movement in Finnish comics history that changed everything.

A WHOLE NEW SCENE OF FINNISH COMIC ARTISTS.

Saskia: If you introduced yourself to someone who didn’t know you: what would you say?

Tommi: I’d say “Nice to meet you, I’m Tommi Musturi.“ I’m a comic artist and fine artist who grew up in a small village in the countryside. I started making music fanzines when I was a teenager: punk, black metal and experimental stuff. I was drawing a lot for those magazines, also comics and illustrations, and we did the layout by the cut-and-paste method. When I went to art school, I met some people who did comics fanzines and I started to focus more and more on comics. I got involved in a couple of anthologies and started to edit an anthology called Glömp. The first issue came out in 1997. In school we had a small comics collective, maybe ten people, who edited three different anthologies together. With these titles, we published 65 different issues in total.

S: Wow, that’s a lot of work!

T: One of them came out every week. It was called Buli but the name changed every issue. The format was small and it didn’t last very long; we made like fifty issues. Fifty copies per week, then selling them for one euro. First we bought beer, but after twenty issues some participants complained and said “Hey, where’s all the money going?” Then we started to buy fanzines, to make a fanzine library for our school. It’s still there.

S: Could you tell me about the other two anthologies?

T: One was called Pole, was edited by Marko Kalliokoski and only lasted five issues. But with Glömp, we continued for twelve years and made ten issues. This small fanzine grew into a 300-page full-colour book with an international cast. I was the editor of that and that’s how I became a publisher of comics.

S: What was the situation for alternative comics in Finland at that time? Did you get inspiration from the Finnish or the international comics scene?

T: For those of us who were born in the 1970s, there was a really big movement in the mid-90s when almost every art school had a collective who made their own anthology. One big reason this happened is that Finland had one of the best comic stores in the whole world at the time. It brought all this material from Europe and North America, for example releases from Drawn & Quarterly, Fantagraphics, L’association, Freon, Amok and many more. They had all the books and magazines. Everybody went to this store; they also had mail order so I ordered stuff from there as I was living in the countryside. This was before the internet so they sent out a monthly catalogue with all the titles. This one store educated a whole new scene of Finnish comic artists.

S: Sounds like it must have been run on pure passion since the Finnish book market is so small and it still managed to get all that stuff here. Do you remember who was running it?

T: It was owned by Timo Mononen, and it was his passion. He brought all this stuff to Finland. Of course they sold mainstream stuff and funded their business with that, while also running a gallery with monthly comics exhibitions. The store was called Kukunor and it doesn’t exist anymore. Finland had a strong fanzine period in the 1980s when hundreds of fanzines were made but it was tied to the punk movement and the quality was not really that good. And of course we had the icons of Finnish comics: Tove Jansson and Tom of Finland. Everybody grew up reading Moomin. We didn’t know the Tom of Finland comics as teenagers, but later it became an important figure as well. And the Kukunor store created a totally new movement in Finnish comics.

S: Back then, did you feel that you and your friends were inventing something new and expanding the Finnish comics scene?

T: No, we didn’t really think about it. You couldn’t study comics then, so everyone was into graphic design, photography or fine arts. Comics was learning by doing for us. It’s still really evident that the people were at art school because Finnish comics are very visual. Everybody tried to invent their own style and narration. Sometimes people complain about that as well, that maybe the stories are not always so good. But the visuals are great.

S: When I look at Finnish alternative comics, or at least the comics in the Kuti magazine, they always strike me as being very different from Swedish alternative comics. The comics in Kuti seem to use much more colour; there’s a different experimentation in the narratives and images, and there seem to be different genres of stories.

T: Yeah, you can see the French art comic influences. I always say that the inspiration for my generation of Finnish comic artists came from Europe mostly, while Swedish artists were influenced by an American style of narration and drawing. But we experimented a lot. After graduating from art school, I moved to Helsinki and the collective around the Glömp anthology kind of disappeared. The anthology became my own project and I started to go a bit further with it. Then lots of artists that used to draw for Glömp started to move to Helsinki. That’s actually how KutiKuti was born, from the Glömp artists in Helsinki.

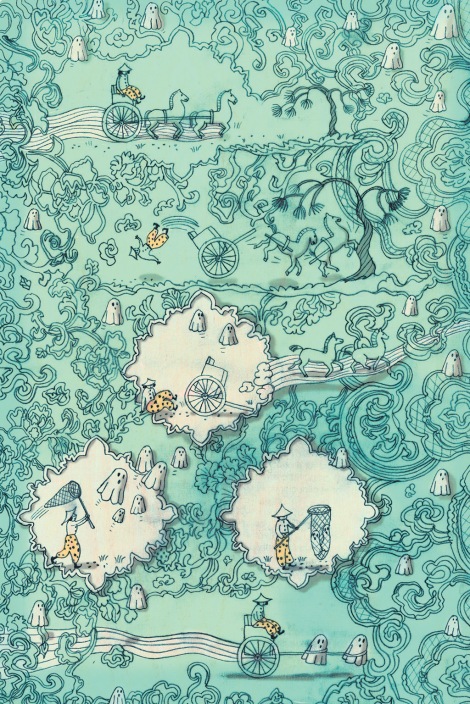

Comic by Terhi Ekbom, published in Kuti.

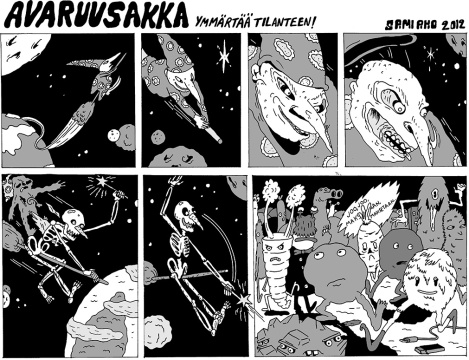

Comic by Sami Aho, published in Kuti. (The page has been cropped.)

S: How did you come up with the idea for KutiKuti?

T: We started the collective in 2005. We were seven people in the beginning; most of them had been in Glömp and shared an interest in experimenting with comics somehow. First we rented a space to have somewhere to work because we had all graduated, hanging out in bars and nobody had a job. Except I actually had a job as an art director, but I quit when we formed KutiKuti. Everybody was doing their comics at home and it’s not so healthy when you sleep in the same room that you work over a long period of time. But even before we had a studio, we had been talking about making a free comics paper. We had met some of the people behind Paper Rodeo, a free comics tabloid from Providence, USA. They really influenced us.

S: How did you meet the people behind Paper Rodeo?

T: At a workshop in Belgium. We went to Antwerp with The Drawing Club to do a two-week workshop with Jelle Crama, a local artist there. He had invited people and from everywhere, with lots of people from the US and Germany, like Paper Rad, CF, Seripop, Mat Brinkman and the people from Bongout. First, we made a book during the week in Antwerp. The next week we went to Holland, to make another book in one week.

S: Very fast pace, sounds like a lot of fun! Would you say that Kuti has a lot of siblings in other countries? Like festivals, comics magazines and stuff working within the same spirit?

T: Yes, Kuti is part of a worldwide art comics movement, including Fort Thunder, Paper Rodeo and Kramers Ergot from the States, as well as Amok and Freon from France who later fused into the publishing collective FRMK, and la Dernier Cri. Art comics have existed much longer in Europe than in the States. It’s a relatively new thing in the US and became visible only in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, there are small American comics festivals that you can find everywhere and a movement devoted to self publishing and fanzines. Every country has their own scene for this now and Kuti was an early participant in this movement. We have been working with a lot of other networks during the years. We brought Le Dernier Cri to Finland and made shows with them. We cooperated quite a lot with Dongery from Norway and went to the same festivals. Paper Rodeo inspired us in the KutiKuti collective to do our own free paper and when other people saw Kuti, we explained how they could do it in turn, financing the paper with ads and cheap printing. I know that Kuti has inspired at least three other magazines.

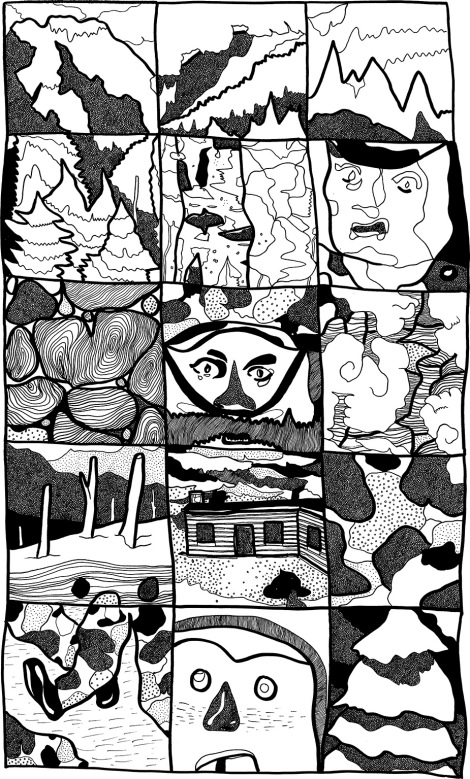

Comic by Jan Oksbol, published in Kuti.

TAKE ANOTHER CLONE FROM THE CLOSET AND PUT THEM TO WORK

S: We don’t have anything like Kuti in Sweden. Could you explain how to do it, if someone there would like to start their own comics tabloid?

T: First you need a bunch of people. Kuti comes out four times a year so if you do it for ten years, it’s a lot of work and you’re not getting paid for it. You shouldn’t start it alone or with just two or three people, you need around ten people that actually work with the magazine. In the beginning, for example, we had two people responsible for the layout and everybody was selling ads. We funded everything with ads back then. Now we have had some government funding for about six years. But half of the money still comes from the advertisements and we have one person who is responsible for them.

S: How did you share the work within the collective in those early days?

T: In the beginning we had one editor. Nowadays each issue has a different editor, which is actually better, since that person has a year to prepare their issue. We translated all the foreign comics into Finnish and had English subtitles further down the page. All the text was hand-lettered by us. But the distribution is, of course, the most important thing. In 2005, we had already been published in lots of fanzines and books, but we could only sell them in art galleries, museum bookstores and independent bookstores in the larger cities of Finland. Our comics were only available in a few places, so normal people couldn’t find this kind of thing. Therefore, our audience was really limited. The original idea behind this free paper was that we could take it anywhere, basically to places where normal people go, and they could find it and figure out what this kind of comics was. We got into the small towns, not just the big ones. Now we have distribution in thirteen towns. The distribution is mostly done by artists.

S: So people take a bunch of Kuti and they go to a place and leave the magazines there?

T: Yeah. We ship from the printing house directly to the towns. In every town there’s one person who is responsible for the distribution. Sometimes people email us and say “I’d like to have your magazine in our town”. Then we ask if they can distribute it, and so we get a new distributer.

S: How did people become so dedicated to Kuti? There seems to be such a big operation and so many people involved from the beginning. It could also have stopped somewhere along the way, with people saying “aaah, it’s too much work”.

T: But that’s the reason why we need lots of people. If you do it with only five people, you can’t do it for a long time, because somebody gets burned out. Now, if someone gets really tired we can take another clone from the closet [laughs] and put them to work.

S: How many people are involved right now?

T: It depends on the issue. Usually it’s about four people from inside KutiKuti and then the distributors from every city.

CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN COMICS

T: With Afri Kuti, the most recent issue, we had lots of people translating from Swahili, Zulu, French and so on. We needed many contacts in Africa who could help us find the artists to publish. Maybe twenty people were involved with that issue.

Cover of Afri Kuti, with illustration by Sergio Zimba.

S: I understood that many of these comics have been published in Europe for the first time with the release of this issue. How did you find the comics for Afri Kuti?

T: We had been talking about an African issue for a long time, but always postponing it, because none of us knew about African comics. We have been very influenced by movie posters from Ghana, and all these African masks, fetishes and statues, things like that. So we were wondering if there are local scenes of people making comics as well. Then I spoke with artist Rui Tenreiro who was born in Mozambique. His comics have been in Kuti and I published one of his books in Finnish, so I know him quite well. He told me he had been holding comics workshops in Mozambique, so he knew a lot of people who made comics there. I proposed to him that he would edit an issue with African artists from different countries. After a couple of months he said yes. So we invited Rui to be the editor and the specialist of the selection. Then we invited South African artist Jonah Sack to be the second editor and he specialised in the South African artists.

S: What kind of stories and styles is represented in this issue?

T: Kuti is always focused on contemporary and alternative comics, so we try to find the borders of comics, somehow. This issue shows contemporary African comics. “Contemporary” refers not only to the style, but also to the kind of stories the comic is telling. Take, for example, Mongo Sisé from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His style comes from the mainstream bande dessinée but his stories are local stories about local life, which make them contemporary comics to me… What was interesting for me was that many of the stories in Afri Kuti show a different Africa than people see on the TV news, for example. The stories are not about war, starvation or total poverty; they talk about daily life, simple problems and stuff like that. I like this, because it feels more real to me compared to many comics from the West, where I might feel like an artist just went to his or her studio, sat down behind his or her desk and wondered “what should I do today?” The African comics that we publish here were not born like that; they were born because of a need to talk about what is happening or some problem.

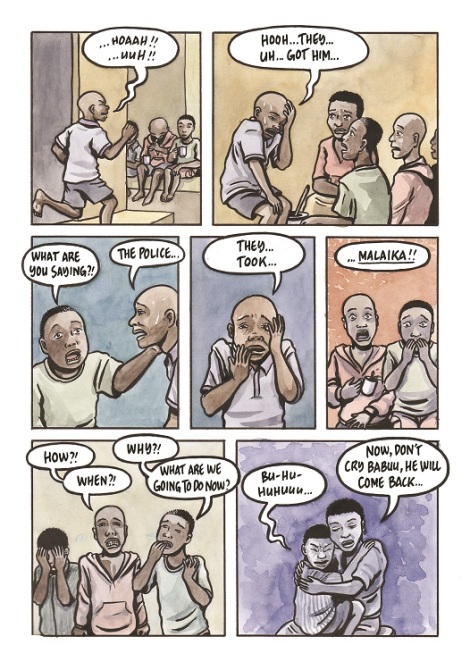

Comic by Sunday Mgakama & Sanna Hukkanen, Afri Kuti (2016).

Comic by Nicko Odingyo, Afri Kuti (2016)

S: What did you learn about different African comics scenes through making this issue?

T: It was a kind of research to see if a contemporary comics movement exists in Africa. It’s mostly local scenes. In some countries there are just a few artists who do this stuff alone. Some artists don’t really know that much about the stuff in other parts of Africa, or European comics. In many of the French-speaking countries in Africa, there’s an influence from the bande dessinée tradition. The work of Mongo Sisé is one example. His style of drawing comes from the bande dessinée of the 1970s even though he wrote his comics in the late 1980s and 1990s. Now he’s dead, unfortunately. Tanzania is a really different example. They have such a big scene that it’s actually sustaining itself. We feature one of the most important African artists: Philip Ndunguru. He sadly died very young in 1986, when he was only 24 years old. He had a really big influence on lots of Tanzanian artists; there is work that is almost a copy of his style and characters and it’s still really popular.

S: How many countries, artists and languages are represented?

T: There are fifteen artists from seven nations. There’s quite a lot of focus on South Africa because there’s a really big comics scene there. Then there are two or three artists from Tanzania; they also have a very active scene. But of course, Kuti is like 28 pages so it’s just a glimpse of what’s happening. We’ve added a list of further reading at the end of the magazine so people can do some more research. Actually, I hope that this project can be the start of something bigger. It’s really difficult to get in touch with all these people, some of them had to be contacted through many people. Actually Facebook was the biggest help with this project. Then there’s the language barrier, of course. But now we have all these connections.

S: And those could be put to use again.

T: There’s also a lot of good stuff that we left out. Lots of really important artists that we couldn’t get in touch with, so we couldn’t publish them. Maybe this could lead to something else, an exhibition or a book.

S: That would be interesting! Are there any female comic artists represented in Afri Kuti?

T: Only one.

INVITE LOTS OF NEW ARTISTS IN

S: Going back to the KutiKuti collective, how would you describe the organization today?

T: We actually changed the whole organisation three years ago. KutiKuti used to be a tight collective of around fifteen people that shared quite a big workspace together. We were all friends and spent a lot of time together outside of the studio as well. But after a while, those people started to have real jobs; some moved away and some people had families. I moved to Tampere. It was not a tight collective anymore. So three years ago, we thought of either stopping the whole thing or changing it. We needed more people, since there was too much pressure on the three or four people who did everything. We decided to continue, to hire a part-time producer and invite lots of new artists in. Now there’s around fifty people involved and KutiKuti is more of a professional association that supports contemporary Finnish comics art.

S: It seems to be a very unique meeting point for artists. Are there also people from a new, younger generation now?

T: The youngest member is around twenty-years-old; the oldest member is around sixty-years-old, and there’s everything in-between. Most of the new people had already been published in the magazine and everybody knew each other somehow, as friends or artists. We try to cover the whole contemporary comics field in Finland and get all the artists who do this kind of stuff in so that we could be a big crowd and do big things together.

Tommi Musturi at the KutiKuti table, Helsinki Comics Festival 2016.

.

TOMMI MUSTURI was born in 1975 in Juupajoki, Finland. He is a comic artist, fine artist, publisher and member of the KutiKuti collective. As a comic artis, he’s known for his character Samuel, a ghost-like creature that travels through colourful worlds and explores different states of mind. His comics have been translated into several languages.

Between 2006 and 2016, Tommi ran the publishing house Huuda Huuda with fellow cartoonist Jelle Hugaerts. Huuda Huuda translated international comic books and graphic novels into Finnish, as well as published artists from the local contemporary comics scene. Tommi has also been the editor of many other publications, including Kuti and the internationally acclaimed anthology Glömp.

In 2015, a definitive compilation of Tommi’s long comic story The Book of Hope was published in Poland, Spain, Germany, Denmark, Finland and the USA. It’s the story of an elderly couple taking a look back at their lives, a contemplation of the lives they have lived and a few deaths.

SASKIA GULLSTRAND is the art director and founder of Underlandet Comics Art Lab. In September 2016, she travelled to the Helsinki Comics Festival to interview the Finnish comic artists Hanneriina Moisseinen, Katja Tukiainen, Hanna-Pirita Lehkonen, Taina Hakala, Johanna Rojola, Tommi Musturi and Amanda Vähämäki. The interviews are part of Underlandet’s ambition to create and share conversations between comic artists.