A conversation with comic artist Hanneriina Moisseinen, written by Saskia Gullstrand. Part 2.

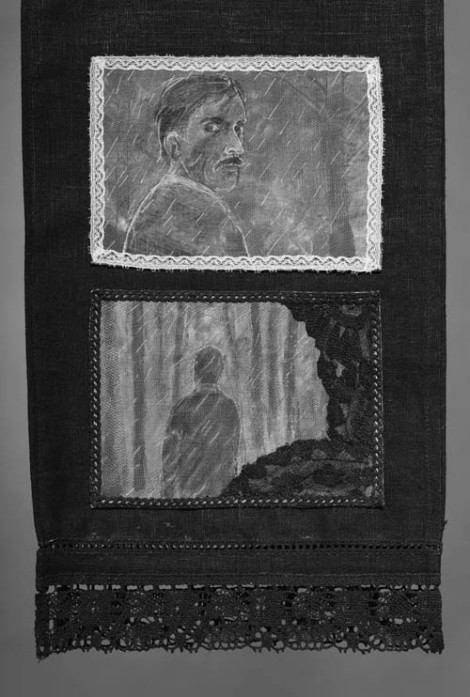

Embroidered page from Isä / Father by Hanneriina Moisseinen.

The first time I met Hanneriina, she was doing embroidery.

We were sitting by a large table in a big dark room, at the 2013 International Network Meeting for Feminist Comics Artists in Hanasaari, Helsinki, listening to people presenting their work and looking at projections of their images and comics. Hanneriina did her needlework, then walked up to the front. She showed us extracts from her book Isä / Father. Page after page with delicate, dark pencil drawings and embroideries.

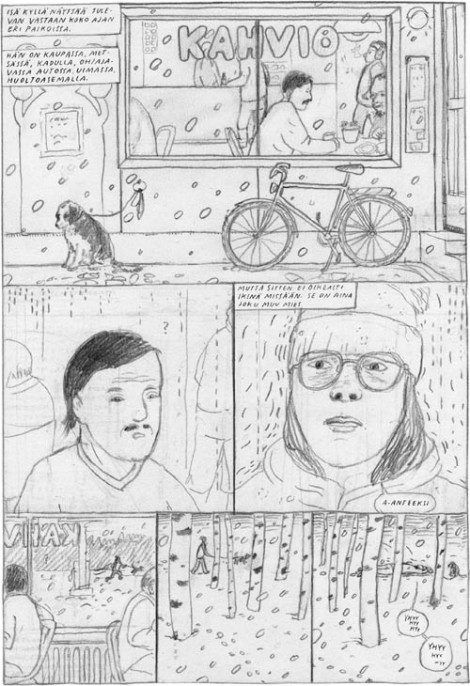

Here’s a scene from Isä / Father:

The sun is sinking down over the edge of a lake, stones like dark bodies in the water. A bear is crying. The tears are made out of shining white pearls that are falling from its eyes in two long strings. They run down over the lake, framing a small boat on the water. The bear tries to cover its face with its paws, more pearly tears falling, falling. They fall like snow on a man lying absolutely still in the water. He’s a father who had disappeared; his family didn’t know where he was. He’s dead. Or rather, we believe he is. Yes, most certainly. He must be. All we know is that by now, in the story, he’s long gone. Lost to his family, without a trace. And his eldest daughter is growing up without him.

Something intimate and unexpected happens in Hanneriina’s comics because she mixes traditional comics storytelling with other media. In Kannas / The Isthmus, she uses archive photography from World War Two to portray the evacuation of the Karelian people who lived on the frontline. In the Isä / Father book, she uses embroidery and painting on fabric.

Again and again, Hanneriina turns to taboo subjects in her art. Exposing a family trauma can be the most forbidden thing of all.

FROM THE TIME OF THE BIGGEST BLACKOUT.

S: In Kannas / The Isthmus, you drew the face of the shell shocked character Auvo as if he were a skeleton. It reminds me of how you drew your mother in the Isä / Father book.

H: Yes… I draw the black eyes to show that the person is really close to death, somehow.

S: Isä / Father is an autobiography about your childhood. It just came out in Swedish with the title Pappa, so it’s available to Swedish readers. How would you describe this book to someone who doesn’t know what it’s about?

H: It’s a story from real life about a family where the father disappears without any reason. He’s never found again. It’s about how the family experiences the loss. About time and the counting of how time changes. There’s the time before the disappearance and the time after.

S: At the end of the book, there’s a scene with a conversation you had with your mother as an adult, where you talk about memories and you ask about her experience. When this scene takes place in the story, you’re already an adult. Was this the first time you started to talk about this in this way with your mother? Comparing memories of how this time was for each of you, when your dad disappeared?

H: There was a seventeen-year-break when we didn’t talk about it at all. Then we started to talk about it. I started working on this book a very long time ago. I spent many years on it. I knew that I was going to do the book. It was in 2006 that I figured out how; I felt that I was capable to do it. After that, it took four years before I could start. Then I really just forced myself to do it.

Page from Isä / Father by Hanneriina Moisseinen.

S: What kind of memory techniques did you use to remember everything when you started working with the book for real?

H: This is basically a memoir from someone who has lost her memory. It’s from the time of the biggest blackout. So I think the embroidery was a really important part of remembering. Then I also started to activate the body memory, I tried to turn off my brain and just draw from what I felt in my body. It was really a kind of physical work. Often I got this kind of physical pain. I felt it in my heart. Also in my throat. When the strongest pain came, I knew that there some memories were coming, and that I shouldn’t avoid them. The body wanted to block the memories from me, but I wanted to process them, of course. I was doing the book to get in touch with the memories that I had lost.

S: Do you think you could’ve got in touch with them if you hadn’t done it through art like this? Do you think you could’ve remembered in the same way?

H: In therapy it’s possible, of course. But I think it was more effective for me to visualize my memories. Also I had kind of forgotten my father completely. It was as if he was a ghost, a black-and-white ghost with no sound or anything. During the process, I realized that he was actually a human being, and that we had been in the same room, and that he had colour and everything. So I got him back as a human being. At the end of the book, there’s this letter where I explain the memories: “If you don’t even remember something, then you’ve really lost everything”. But I got back my memories, and that is what I was aiming for.

S: This book made me think of how losing memories and blocking memories can happen to different degrees. For example, when one has experienced violence in childhood by an adult or family member, there might be all different kinds of memories of this person, both as an abuser and as something else that often exist in two very separate storylines. To be able to connect these images and make a whole person out of the fragmented memories can be so liberating. I know this from my own experience. Both of the books that we’ve been talking about now are about memory, but in different ways. Kannas / The Isthmus is about collective memory, and Isä / Father is about a personal memory. You didn’t live through the war yourself, so how did you access the memories that Kannas is built upon?

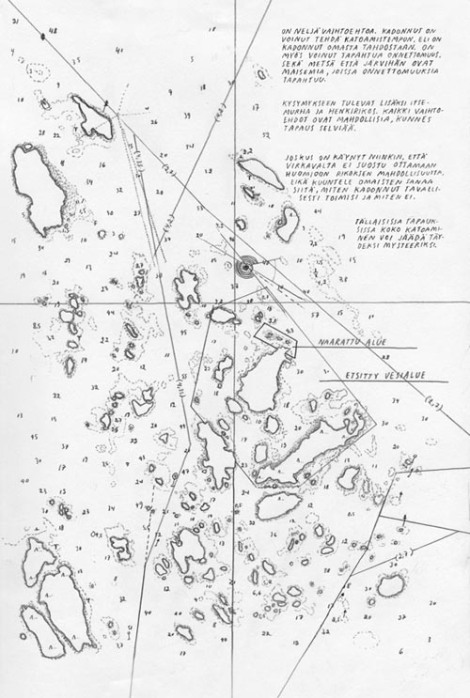

H: Kannas is a very collective story. The Finnish literature society has archives of all kinds of… it’s an archive of traditions and for example the oldest known songs in Finland, but there are also memoirs and they arrange collections of, to name a few topics, how people remember or think of forests, Koskenkorva vodka, war, pregnancy, or evacuation. They have open calls where people can participate and contribute to the collection of stories. So I had a pile of books this high [shows with her hand], over 3000 pages to go through.

S: Was it easy to read the handwriting?

H: Not always. I read these books and I listened to old magnetic tapes and made notes. The archive photographs are all on the internet. Some of these pictures have been published for the first time in this book.

THE EMBROIDERED PAGES CHANGES THE RYTHM.

Page from Isä / Father, by Hanneriina Moisseinen.

S: In Kannas, you combine war photographs with classic comics panels as a storytelling technique. You’ve done a similar thing before in Isä / Father, but with embroidery instead of photographs. What does it mean to you to work with this kind of technique?

H: I’m interested in the possibilities of comics and the different layers of storytelling. For example, in Isä / Father, the embroidered pages are the more subconscious level of the story. Those are the parts where the reader can sink into the pain of the characters, or wherever they want to sink. It’s beyond-the-time type of storytelling. You’re supposed to read them more slowly than the drawn pages. It changes the rhythm. I’m interested in time and space in comics.

S: Do you think there’s a relationship between the rhythm in reading and evoking in the reader a feeling of being in a different state of consciousness? Like being in a dream, almost, though not really a dream. That the rhythm of the story speaks to something the readers have experienced themselves previously in life. Do you think it could be true that it works this way?

H: Something like that, yes.

S: Last time we met, we spoke about how you work with comics exhibitions in a quite unusual way. Would you like to explain more about what you have done with exhibitions?

H: The embroidered pages of Isä / Father have been in many exhibitions, maybe twenty all in all, in many different countries. I made those especially for exhibition purposes. With Kannas... I made the whole thing thinking that it would be shown in exhibitions. That’s the main reason why there’s so little text. Because in exhibitions, people don’t necessarily read text. I wanted to do exhibitions where it would be possible to read the whole thing. From Kannas I made two exhibitions, one with Maria and her cows as main characters, and the other one with Auvo.

S: Do the exhibitions interlink? Like, are they being shown in the same place, but in two separate rooms, one for the Maria exhibition and one for the Auvo exhibition?

H: No, they were shown in two different galleries and at different times. The first exhibition was in January and the second one in May. I did two exhibitions because it might be too much to read 240 pages at once in the exhibition space. This summer I’ll combine the stories together differently, as a larger exhibition in an art museum in eastern Finland.

S: How did you use sound during these exhibitions?

H: There was a special soundtrack for the exhibition. I had a radio that looks similar to this one [points it out in the book] in the gallery space. The real radio was used as a model for the one in the book. The text here, that you can see coming as sound from the radio in the comic, is from the Finnish broadcasting company Yle’s archive. It’s a real audio footage from 1944, with a journalist following the evacuation. The radio in the exhibition space was playing the same sound so you could listen to it and read it in the story at the same time. Besides playing this radio footage, there were also soundscapes, made partly of archive material and partly of sound composed by Eero Grundström and Anne-Mari Kivimäki, whose doctoral thesis was the inspiration for the book. There’s lots of songs and music in the soundtrack. Anne-Mari and Eero where both playing live performances in the exhibitions. [LISTEN HERE]

S: There are characters singing in the book as well.

H: When I was in the archives, there was a scene that was repeated over and over in the memoirs… When people were gathered at the train stations to evacuate – the last moment they were all together in Karelia – the men would take their hats off. Together they sang the song Karjalan kunnailla [On the hills of Karelia]. And then they got on the trains and left, the border closed and most of them could never return to their homeland. Reading this made me cry so much! One evening, I was in the archives, and there was a very good description of this kind of scene in the book I was reading. I looked at my watch, and it was late, the archive had already closed for the day, but I just sat there crying and crying.

[Hanneriina leans over the table, showing tears flowing down her face with her hands].

H: Five minutes later, I went to return the books and the very friendly archive person said “actually, we closed five minutes ago”. Then he had a look at the books I was holding, and then he said “Ok! All good, it’s no problem!” [laughs].

S: He knew it was some heavy shit. [laughs]

H: My whole face was red from crying.

S: The joke that the other milkwoman tells to Maria on page 106, did you find it in the archive, or did you make it up?

H: It was actually from a Karelian joke book. I think Karelians are about the only people in the world who have released a joke book about their refugee experiences, twenty years after they had to leave their homes permanently.

THE PEOPLE WHO HAD A HOME DIDN’T NECESSARILY WANT TO SHARE IT.

S: At the beginning of our conversations, you mentioned that you don’t like Finnish war comics. Why?

H: I’ve tried to read a couple of them… [laughs] It’s like a combination of the Finnish war propaganda and some kind of admiration for American superhero comics. The result is something horrible.

S: Who are the heroes of those comics? Is it the common soldiers, the generals or someone else?

H: Once I read a comic book about Simo Häyhä, who killed 200 people, just with a rifle, during the three months of the winter war. The comic is a heroic story and he’s made into this great hero, because he killed so many Soviet soldiers. In the end he loses part of his jaw. He was also one of the evacuated ones, a Karelian sharpshooter.

S: Talking about war propaganda… How is it in Finland nowadays when it comes to nationalism and militarism?

H: There’s lots of prejudice against refugees escaping war and coming to Finland. Some neo-Nazi movements are growing. The government is taking some benefits from the poorest people, while the populist racist party says that it’s the immigrants who cause all the problems. So the poor people start to think that the immigrants have taken the two euros that they lost in unemployment benefit.

S: Kannas is about refugees who have to leave everything because of war. The quote on the back could be said by many who are stranded outside of the borders of the European Union today. “We had to leave absolutely everything!” How has it been for you to work with this project now, when all these things are happening?

H: People weren’t speaking at all about the refugee crisis when I started the book, but then the discussions began during my work process. People are talking a lot more about the Karelian evacuated people nowadays, trying to remind each other that actually it was just 70 years ago that 12 percent of the Finnish population had to leave there homes because of the war. Many people have got a Karelian grandma or grandpa, it’s estimated that of the population of 5,5 million Finns, about one million have got their roots in Karelia.

S: Where did the Karelian people go, when they lost their land?

H: All over Finland. If there was a village, the government decided that the people of this village should move as a group to another village in western Finland. So people would know each other and have some support. Not all the people knew where they were heading when they left their homes. They could also be taken to one place, and then given a new destination. Of course they were free to go anywhere they wanted. Some people had relatives in western Finland and they went to them instead.

S: Where there conflicts between the Karelians and the other Finns?

H: Exactly the same kind of conflicts that there are nowadays. The people who didn’t have to leave their homes had great prejudices against the people who came from elsewhere. The Karelians where called ”ryssä” which is a bad word for a Russian, for example. They were treated almost like a second-class citizens. The people who had a home didn’t necessarily want to share it with the people who didn’t have a place to stay.

S: I was thinking… Even though the frontline wasn’t everywhere, Finland was still generally under attack and mobilized during this time. Everybody experienced the war in so many different ways, like the lack of food and everything. Did these shared experiences also spark some generosity towards the refugees?

H: Some people where friendly and helpful. From the beginning, there were a lot of romances between the refugees and the people of western Finland, as there were also romances and other incidents between the Finnish soldiers and Russian Karelian women during the war time. But the attitude has been exactly the same as towards refugees nowadays. There were a lot of problems.

S: Then it’s even more heart-breaking that the Karelians had to leave again, after they returned home in the end of the war. It’s just horrible. Earlier, we spoke about elderly people who have lived on a certain piece of land, how they refuse to leave that land even when someone is taking it from them. People also seem to have such a strong reaction towards sharing their land with other who have been forced to leave and evacuate. Why do people sometimes feel so strongly against sharing land with new people?

H: They are afraid of something. Maybe that they’ll lose what they have. It’s a materialist fear, I guess.

S: That also reminds me of a part in the book… maybe it was on the radio, where they say that possessions can be replaced, but a life that has been destroyed can never be replaced. So this is also addressed in the book.

H: There are these ladies, the same ones that say that they had to leave absolutely everything. On the radio they say that they are kind of longing for one small practical thing that they had to leave behind, like their better shoes that would have been better for walking. And then… it was also a part of the war propaganda, this radio program. It has the tone of putting things in a bigger context.

A HOMELESS BOOK COLLECTOR

Page from Isä / Father, by Hanneriina Moisseinen.

S: What is your next project?

H: During the summer and autumn, I wish to have a bit of holidays. For the years 2018 to 2021, I got the state grant for my artistic work, which I’m very happy about. Currently I am working for an animation film about a wanderer who loved books and happened to be the one to save the oldest Finnish literature with his amazing book collection. The academy library in Turku had burnt down in 1827 with 40 000 books, and there was no other collection to replace it in the whole country. The man, Matti Pohto, whose father drank away their house and who had to beg for his living when he was a kid, became a homeless book collector who put all his money and made every effort to collect books. He succeeded to gather the most valuable old books in Finnish, which he donated to the university library that was re-established in Helsinki, and is now the national library. Pohto died in 1857, when a worker man he didn’t know hit an axe to his head, in a house where he was staying. The animation will be out in September.

S: Have you done animation before?

H: I made one animation from this scene in Kannas where the cow gives birth. It’s on Vimeo. [WATCH HERE]

S: You trained as a visual artist before you became a comic artist. Could you tell the story of how you became a comic artist?

H: I made some small zines when I was in high school. Then I was at a punk festival in a little forest town in eastern Finland. I was selling this bunch of zines to people for very little money. There was also another guy there selling his stuff, Tommi Musturi. We traded our fanzines; he had an ancient Glömp anthology that was also made on a photocopier. Then he asked me to do comics for the next Glömp, which made me happy. The same year, I went to art school and met Tiitu Takalo. She was in my class and she was really into zines as well. She wanted to make a zine with only female comic artists. Both Tommi and Tiitu said that I should do more comics. Then I made one for Glömp that became kind of popular, people started to speak about it.

S: What was it about?

H: It was called Outokumpu-Jouensuu, where there’s this guy who doesn’t have a wife. He lives in the forest with his mother; they have a garden where they grow courgettes. One day, they find an enormous courgette there. This is a good sign for them, so they go to the nearest town to look for a woman for the man.

S: Because he’s obviously ready to impregnate someone!

H: They find the fertility symbol in the garden. [laughs]

S: What if that was always how you knew, that this is the time! Like “now I’m ready, I’m ripe!” I wonder how he approaches the women in the town. Is it “hi, I have this giant courgette, do you want to meet it?” Does he find someone in the comic, or does it end before we know?

H: It ends without answering this completely. It’s a different kind of ending; after some struggles and after trying to convince a woman that she should follow him to the countryside and go to the sauna with him, he goes to another place. He starts running, then he sees somebody who’s going to swim. He approaches the person and asks: “Are you a boy or a girl?” He is very interested in this person. Then it ends.

Hanneriina’s book Kannas / The Isthmus will be published in Swedish in the future, with the title Näset.