A conversation with comic artist Amanda Vähämäki, written by Saskia Gullstrand.

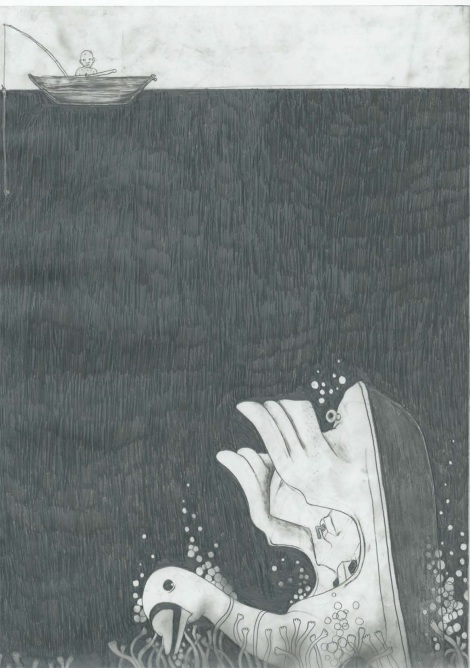

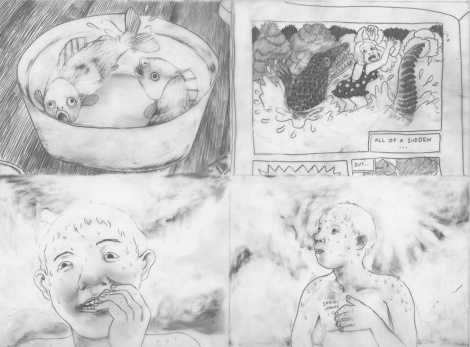

Page from the comic book Cani Selvaggi by Amanda Vähämäki

Amanda Vähämäki is a master of strange stories.

When you enter the world of her images, the uncanny and absurd are never far away, lurking in the familiar scenes of daily life. Like when a young girl is lying on the sofa, watching television, with a small ghost resting on her belly, sucking a feeding bottle like a baby. Or in another story where the librarian who’s spending the weekend alone in her home suddenly slips into an otherworld and receives an unlikely guest with an important message.

Amanda’s drawings are precise and sharp, but she also uses pencil in the way some people use paint, smearing and smudging it into landscapes, objects and characters. Many of her stories seem to play out on the border between known and unknown reality.

I met her in Helsinki to talk about the fantastical elements in her stories, the story universe she made up together with friends as a child and a very special arts teacher in Bologna.

AT ONE POINT WE MADE THEM HUMAN

S: If you were to present yourself to someone who doesn’t already know you, how would you describe yourself?

A: Usually I just say that I make comics. Normally they start asking me what kind of comics? It’s difficult to answer. Sometimes when children ask me that, I say that I make my own comics, not Donald Duck comics. Then they ask me: “Who is your character?”

S: Do they get a bit confused if you answer that you don’t have one character?

A: Yes, but I think would be nice to have a character. That’s how I started when I was ten-years-old. I created my own universe with my friends. We drew characters and we made charts of their facial expressions on little pieces of paper.

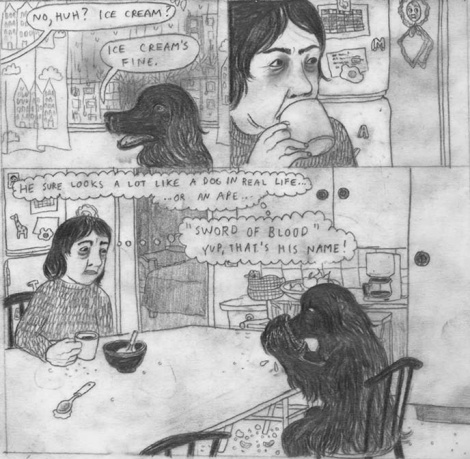

Page from the comic book Cani Selvaggi, by Amanda Vähämäki.

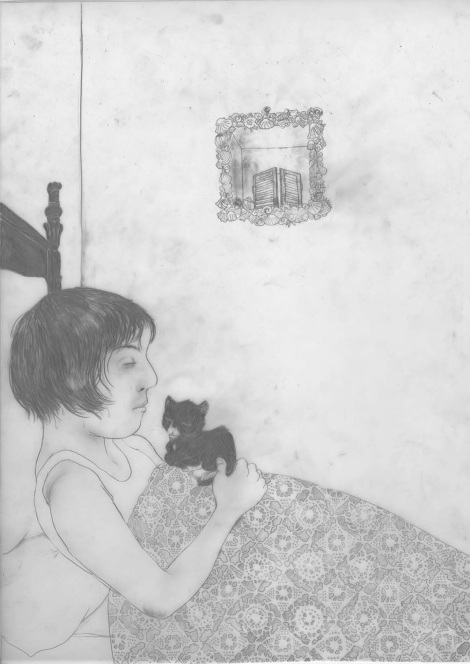

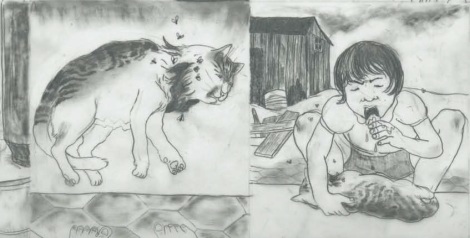

Panels from the comic book Cani Selvaggi, by Amanda Vähämäki. This image have been cropped.

S: What kind of characters did you create?

A: I had an Arctic fox. It was kind of a fantasy world. Lately, I’ve noticed that it had a lot of things in common with Babar. Not stylistically, but there are kings and kingdoms. It’s all somehow out of place as well, like Babar. We were really big Narnia fans and we liked the fact that somebody is king, without having known about it before themselves. The first comics were developed on that theme. It was a furry universe; everybody was an animal.

S: Who were the other characters?

A: Teddy bears and foxes. Some of them were really cute.

S: Who was the king?

A: My Arctic fox was the king.

S: Are those stories and characters still somewhere in your work?

A: Somehow, yes, because we started when we were nine- or ten-years-old. As we grew up, the characters developed different kind of dimensions. At one point, we made them human. We decided that they were not animals anymore.

S: How old where you then?

A: I think eleven- or twelve-years-old.

S: So you kept these characters for several years and transformed them into people?

A: Yeah, then there was this alternative universe where they lived and… Actually, in my comics I have used characters that I designed when I was a kid. As teenagers, we started to make lots of notebooks written by these characters. I still have a huge IKEA bag full of those books. Many of them are unfinished but some are written in from cover to cover. It’s like they’re diaries but with pictures and some borrowed stuff, like poems; we put some poems in there that we thought were good for the story. So actually the people from that feature in the Mother’s Day comic are from a diary.

S: Do you sometimes flip through them even now and pick out things?

A: No, it’s painful [laughs].

S: It reminds me of the fantasy world of the Brontë sisters that they created together as children. I was always fascinated by the idea of four siblings on a moor somewhere, very isolated, but they shared this incredible fantasy world.

A: But I was not very isolated. In one way, yes, because I was not so much into the dynamics of the classroom, and I just had two friends and that was enough. We had this narrative universe that we shared.

S: So both of them was involved with this world?

A: Yes. They had their own characters.

S: Was anyone else invited apart from you three?

A: No, it was really exclusive.

REAL LIFE DRAWING, COMIC STYLE

Panels from the comic book Cani Selvaggi, by Amanda Vähämäki. This image have been cropped.

S: Somewhere, you said that an Italian art school professor taught you that the only thing you could do properly was comics. Is that true?

A: After high school, I went to Bologna to study art history. Then I applied for their fine arts academy and… I don’t know what I planned to do, but it wasn’t comics! When I created all the characters and diaries when I was younger, I wanted to have an animation empire, like Disney… but it would be my stories. So that was the dream, but when I went to high school, I didn’t draw that much. I started to write instead, so that was one possible path. But in Bologna, we had this anatomy professor who had his own thing going on, and whose lessons where maybe the only obligatory course in the whole programme. He made sceneries in his home. He would paint the backgrounds and had two models, and he’d make them pose for ten minutes, five minutes, and you had to draw the models and sketch the scenery. You had, like, five or eight poses, and it would be a story. He would say the lines that the characters where saying.

S: So that was like real-life drawing, but comic style?

A: Yes.

S: Where the models naked?

A: No, he also had costumes for them. He was really into anything old, like film noir or early animation… Some of them where really silly and annoying stories, and there where recurring characters in the stories.

S [laughs]: This is really funny! He had all of his students doing his comics for him.

A: At the end of the year, you had to make illustrations or comics out of those sketches. He had an animation class as well; he had a collection of Super 8 films and showed those. He would also show Norman McLaren films and experimental animation. There’s a future film festival in Bologna, which also has an animation part, and a famous children’s book fair with illustrators showing their work. Also, there was a culture association that was initially only concerned with children’s literature, which founded the BilBolBul festival.

I LIKE HAVING A FANTASTICAL ELEMENT

S: What is your process of ideas when you make a comic, like Bullefältet/The Bun Field, for example?

A: That one is so old, I don’t really remember… I started to make that one for me personally. It was a notebook I carried. I started to make it just for fun. I always say that it’s autobiographical somehow. It’s really different from most of the stories that I’ve written. That was also a time in my life when I always wrote down the dreams that I had. Nowadays I wake up and I don’t remember any of the dreams. But also… I got so many comments on how dreamlike that comic was, that I started to think “oh, dreams”….

S: It has a very dreamlike structure. But, at the same time, one could also say that it’s like a movie. I think of David Lynch films when I read it. There’s this character who starts out their day and then things turn more and more uncanny. Creepy things begin to happen. All of it is also normalized in a sense… and then there’s this violence. It’s such a bloody comic as well. With the character falling on her head and bleeding all over things. If you don’t make dreamlike comics anymore, what are your comics like today?

A: I like having a fantastical element. But I don’t really know what it is there for. I like to have it just for the sake of it. But maybe it still stands for something.

Panels from comic Contains Small Parts, by Amanda Vähämäki. This image have been cropped.

S: What does that look like in the comic?

A: I made a comic called Contains Small Parts.

S: Like on a toy package when you don’t want the child to choke?

A: Yes. It’s about a librarian who’s also a divorced mother. Her kids go away for the weekend and she’s left alone. Then she enters the other world, the fantasy world. Most of the reviews that I’ve read thought that this is the fantasy world that this mother escapes to. Like, this place that she wants to go to. But that was never my intention. The intention was that she does not want to go there, but it happens anyway.

S: Does she go there accidentally or is she drawn in there against her will?

A: It just happens accidentally. There’s not so much drama in the comic, it’s more like a sitcom.

IT IS NOT THAT SATISFACTORY TO HAVE A BEGINNING AND AN END.

Comic panel by Amanda Vähämäki. This image have been cropped.

S: What comics are you working on now?

A: I’m making a prologue for that comic, about what happened before. Also, I’m working on a longer historical graphic novel together with Sami Aho, another Finnish comic artist. It’s… well, it’s not a real murder mystery, but it’s based on this real event in the 1930s in Helsinki. I was working on it for a long time without much progress. Though hopefully this year [laughs]… Originally it was my own project, but then I was concerned about not being able to make it violent and disgusting enough, so I asked Sami for help. We were talking about this case because it’s this rather famous case in Finnish crime history. Sami said that someone should make a comic out of it and I told him that I was trying to do that.

S: How did you ask for help, like “Can you make this more gory”?

A: We were talking about the difficulties that were coming up, how I was thinking about the project. I don’t want to tell only this story, I want it to be part of … there were other interesting things going on in Helsinki and Finland that particular year, like the rise of the extreme right.

S: Is there a main character? Or does the story follow several different people?

A: We decided there would be lots of characters. Because if there’s only one, there’s the risk that it turns out too detective-like. And we don’t know how to write a detective story.

S: Yes, if you work with that genre, you need to have clues so that the audience can figure out the crime.

A: And you need to have a beginning and an end. Something I don’t really care about in storytelling is… oh, I guess I do care, but, the thing that happens to me really often when I finish a comic, is that other people ask me “Will it continue?”, but it won’t. I don’t like the storyline to be too traditional. In my own work, I feel somehow that it’s not that satisfactory to have a beginning and an end.

S: Do you think you have another kind of narrative? When do you feel satisfied with a story?

A: I don’t know, this is difficult to say in English. But it’s also difficult to say in Finnish. I have been thinking about this a lot, because also I’ve been trying to figure out what’s wrong with me [laughs] and whether the stories should be constructed in a different way. There’s some planning and there’s some improvisation, and often it turns out this way. And at some point, I can see that, yes, this is finished now.

S: So it’s more a feeling that you get, when it’s done it’s done and you just know it?

A: I don’t know, I have to think about this, before I can express it.

S: That’s ok… I ask so much about your work process because I think it’s so fascinating to see how other artists work. When I work with my own ideas, I feel that I’m making a skeleton. The core scenes of the story are like different body parts and they have to be related with one another. I know that the story is complete when I feel that it has a functioning skeleton that can move by itself, when there are no loose ends – the head is attached to the spine and the spine is attached to the hips and the hips is attached to whatever kind of legs this story is having. Then I understand why things are happening the way they are and it can all move and work together. After that, I can make the comic. But lately, I’ve become interested in how to make stories really fast, not asking why a certain image is there. Do you question your images and why you have them in the story?

A: When I work, I’m so slow that I have the time to think about the why of this and that image. Also too much. I can think “Does this make any sense? Maybe not!” I have a lot of uncompleted work, just like when I was a kid. But if I’m committed to something and it has to be printed somewhere, then I have to finish it. There’s the deadline. And that’s a good thing, I think.

.

AMANDA VÄHÄMÄKI was born in 1981, Tampere, Finland. She began publishing comics in 2004 via the Canicola collective in Bologna, Italy. Her drawings are suggestive and done with a thin pencil line. A strange feeling often lingers in the atmosphere of her images, as if something unexpected is just about to happen in the midst of everyday life.

Her graphic novels has been published in several countries, and her short stories have appeared in international anthologies like Glömp, Orang, KutiKuti and Galago.

In 2005, she won the Swiss Fumetto International Comix Competition. Her work has been translated into five languages. In 2012, she was chosen to be the official festival artist of the Helsinki Comics Festival of that year.

SASKIA GULLSTRAND is the art director and founder of Underlandet Comics Art Lab. In September 2016, she travelled to the Helsinki Comics Festival to interview the Finnish comic artists Hanneriina Moisseinen, Katja Tukiainen, Hanna-Pirita Lehkonen, Taina Hakala, Johanna Rojola, Tommi Musturi and Amanda Vähämäki. The interviews are part of Underlandet’s ambition to create and share conversations between comic artists.