A conversation with visual artist Katja Tukiainen, written by Saskia Gullstrand.

Studio of visual artist Katja Tukiainen and comic artist Matti Hagelberg, The Cable Factory, Helsinki. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

I’ve entered a gateway to a world of pink.

This gateway was located on the fourth floor of the Cable Factory cultural centre in Helsinki. A pale, heavy door in the narrow corridor. I opened it and entered the studio of visual artist Katja Tukiainen.

Katja Tukiainen can paint a rainbow of pink, full of electricity and shadows. She is wellknown for her use of girly esthethiques, and a lush, varm colour palette, rich with shades of pink and magenta. She has created several comic books for adults and children, as well installations, paintings and animation, that has been shown in exhibitions world-wide. But I also think of her as an innovator, who has experimented with the ways that comics can be used within exhibition spaces, byt turning them into installations and site-specific narratives. Her installations include paintings, light pieces and dolls, yet the final works always involves a narrative element. Katja’s work can be a huge inspiration for anyone experimenting with how comics could be shown in exhibitions. During the past two years, my own work have been focused on trying out different ways of using comics storytelling in a space. So of course I had one million questions for Katja. When I wrote her and suggested an interview, she was kind and welcoming, inviting me to her studio at the Cable Factory in Helsinki.

On Friday, 2nd September 2016, I went through the gateway to her workplace, prepared with questions about Katja’s world of images and her diverse ways of making comics. Her studio is splashed by paint blotches; they are absolutely everywhere, as if paint has at times dripped down from the ceiling and walls of this room like rain, revitalizing the energy and creating growth. Katja shares this room with her husband, the cartoonist Matti Hagelberg. His work table is an island, surrounded by a wall of tall bookshelves. Katja’s work fills up the rest of the space; paintings, light installations, gigantic mannequin dolls: Her work is everywhere – on the walls, the floor, on the other tables crammed into the corners of the room.

She had promised me 45 minutes for the interview, but in the end we talked for hours about her recurring characters, censorship of her art and what emotions and secrets that can be awakened by the colour pink.

HOW TO BE THE GIRL I AM, IN MY WAY.

S: If you were to introduce yourself to someone who doesn’t know you, who would you be?

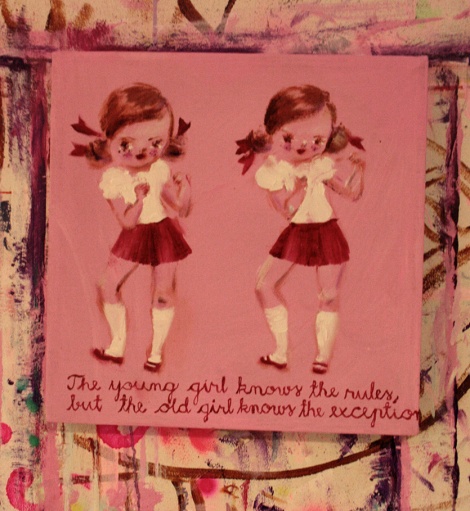

K: I’m Katja Tukiainen and I’m a visual artist. That includes everything: comic artist, painter and more. I also use words in my paintings; words are really important to me.

Katja Tukiainen and Matti Hagelberg in their studio. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

S: Can you tell me about Mademoiselle Goodheavens? Who is she; where did she come from?

K: She is this girl character, that I created in 1991. The inspiration came from my childhood. When I was small, my grandmother lived with us. I had long hair that she braided every evening, to stop it getting too messy; sometimes she made the braids like pretzels. When I started to draw Mademoiselle Goodheavens, I thought it would be funny if the braids could move like animal ears on the girl’s head. The ears also reminded me of Mickey Mouse. A friend made a Mickey Mouse tattoo for me when I was a sixteen year old punk girl, using a sketch I drew myself. I wanted something very raw, so this old-school Mickey Mouse image was good; I choose it instinctively. It was a radical thing, because when I was a little girl, my mother always told me not to get any scars, otherwise I could not become a model. But when I got the tattoo, she did not care anymore; she must have given up on this dream by then, because I was not tall enough and did not look like that kind of woman [laughs]. Rather, looking back at it now, I think she was happy to see I did things my own way. Since I reached my teen years I remember she always encouraged me to be myself and not to care too much what other people think of me. That was important. My mom and my dad were proud of me even during my most boyish looking punk style years.

S: Do you think there was a difference between what a girl could imagine herself to be when your mother was young, compared to when you were a teenager?

K: Yes, because she grew up during a very different time. It is interesting, since my grandmother was strong and told funny, naughty jokes. She worked as a nurse on the battle front during the Second World War and saw a lot of things. My grandfather was a young soldier who got addicted to medication during the war. When peace came, he could not stop using it and he suffered from post-traumatic stress. It was horrible. My grandmother was a seamstress, who went around all the small villages with her sewing machine. She was so strong that she decided to divorce my grandfather and live alone with my mother, who was four years old by then. Later, my grandfather married again and had five more daughters; my mother also knows these half-sisters. So my grandfather was happy later [laughs]. My grandmother lived with us, and she didn’t care about the limitations of what was women’s work and men’s work. She was both father and mother to my mother. But maybe my mother, for her part, was more traditional. But then, the parents grow with their kids, and I am thankful we found the way together. Kids are challenging teachers for the parents. And I always knew what I wanted, how to be girl I am, in my way. The Finnish society was really traditional until the 1960s when a lot of things changed. My mother studied at university though, which was not so common for women back then. She is a pharmacist and my father is a pastor and therapist. He worked in a hospital and a psychiatric hospital, talking to the patients about personal things. I never met my grandfathers, nor my mom’s dad or my father’s father, who was also a pastor. But I heard many stories of both of them. It’s important for me to know them through these stories.

THE FEELING THAT I CAN DO A LOT OF THINGS.

[Katja guides me around her studio. It is pink, and full of objects. A giant doll is lying on the floor, a mannequin of Mademoiselle GoodHeavens. Katja shows her to me.]

K: It’s so hard to make the hair. I will work a bit more on it in the coming days.

S: What is this object made of?

K: I made a very rough version out of the yellow foam that is used for insulating houses. Then I used fibre glass. It is like a textile, you know, but horribly itchy. After that, a resin-like kind of stuff to make the surface. I was working on it for a week with a machine and then I painted it. Now I am going to give her dental braces, eyes and eyelashes. It will be finished in two days.

[The mouth of the doll is open, revealing her teeth. ]

S: I love her mouth! Did you have dolls with teeth showing when you were a child?

Mannequin body by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand.

Mannequin head by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand.

K: My mother had some fantastic old dolls that were really tiny. I love dolls. As a girl, I made small dolls myself with my granny, who taught me how to sew. Now, I have made several large dolls with this character. Some of them were for the exhibition Girl Evacuees, with Finnish designer Samu-Jussi Koski. He made beautiful black dresses for them, so I had to make their arms removable, otherwise we would not have been able to put on their clothes.

S: I saw a picture online. One of the dolls is hanging really high up in the ceiling, but her dress is long and almost touching the floor. She’s floating like a ghost. You work through a range of different media, as you said before. How did you learn to use all of them?

K: I studied to become an art teacher in the University of Art and Design in 1990 in Helsinki. I didn’t like the program though, because I wanted to be an artist, not a teacher. But my aunt and uncle were both artists and I knew how they struggled to get by, so I went there to learn a so-called “real profession”. Looking back at it though, it was very good for me. We had to learn about clay, plaster, sculpting, photography and painting so that we could teach these media to our students. Knowing about all these different materials gave me courage and the feeling that I can do a lot of things. I also got this from my family; my father always had projects going on in the garage at home and my grandmother was sewing. I wasn’t afraid of any kind of material, and the school encouraged me even more.

S: In art school, students sometimes get so scared of doing anything, because they want to be a genius and prove themselves. Do you think the art teacher program was a good way of avoiding this?

K: Yes, I think so. I was twenty when I started. I was really nervous about what the professor would say about my art, but I still did the work I wanted to do. After four years at the art education programme, I went to Venice to study at the painting department of the Academy of Fine Arts. I was there for a year, focusing only on my painting. Then I felt ready to take all the feedback from my teachers. In 2007, I went back to study in Helsinki, to do a Master’s at the Academy of Fine arts, because then I was ready for that. So it was a good path for me.

S: When did you start publishing comics?

K: I published my first stories about Mademoiselle Goodheavens in an anthology called Naarassarjat in 1992. “Naaras” means biological female, like you might call a female dog, and all the participants were women artists. Then I was published soon again in another women-only anthology called Sarjakuvastin. When young girls like me started making comics in 1991 and 1992 in Finland, there was this group of men who were older than us and had been making comics for a longer time. We were in our twenties and we thought they were dirty, old men who never washed or took showers, that they only ever drew comics. They were probably only ten years older than we were at the time! [laughs] But we thought “gosh, they are horrible”! And they were sometimes a bit aggressive towards us. Young women artists were a danger to them. They said that our drawings were bad and so on. It’s funny, because it’s not like that anymore. Today, older comic artists like me don’t say to younger people that their comics are bad. No-one is like that nowadays.

INVITING THE VISITOR TO WALK INSIDE THIS ATMOSPHERE

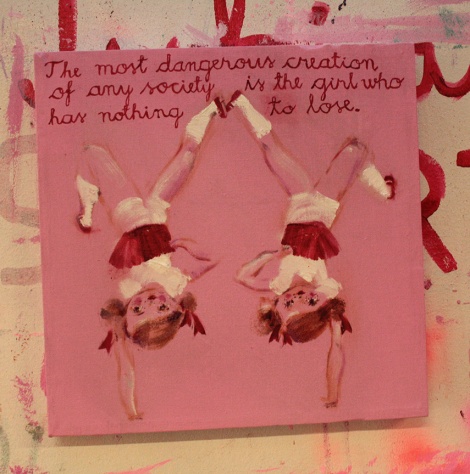

Narrative painting by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

S: I’m really interested in the hybrid art form you have created in various exhibitions by combining installations and comics. For example the Paradise K Kidnap-installation that you showed at the KIASMA museum of modern art in Helsinki in 2012, as part of the Päin Näköä!-exhibition. You and Matti were selected together with a group of other comic artists to show your work, and you made a new site-specific installation for them; using paintings to create a sequential narrative with text and images. I’ve seen pictures of it online, and it’s so cool! The paintings surround the reader from all sides and tring lights snake their way over the walls; framing the paintings and forming words on the wall. Paradise K Kidnap features a squad of your girl-characters, hanging out in a paradise setting, being bored. They attack a unicorn, chain it to a tree and force it to give them the key to happiness.When you are creating an exhibition like that, what is the work process like?

K: That process was a bit crazy…

[Katja turns to her husband, who’s drawing a comic at his own work table.]

K: Matti, when we were invited to take part in the exhibition, didn’t I tell you from the beginning that we wanted the space with high ceilings, Studio K? It is the most interesting room in the museum; fourteen-metres-high, with a balcony on one of the walls. How did we get it?

M: It’s really the best space, that’s why we wanted it. There are lots of other rooms with lower ceilings that are not as interesting. We just told the museum that we wanted it. We made a plan really early on, on how to use the room; how we wanted to divide it and what we wanted to do. But also, of all the particpating artists we had the most experience of working with a space. I don’t think the other artists had a similar inclination to think about a comics exhibition in an installation kind of way.

K: They were not interested in the place as a space in itself. Some comic artists just focus on the book. But I had worked with spaces before and I really wanted to build something in this room. When I got the idea for Paradise K Kidnap, we decided that Matti could hang his originals below my paintings. Then, when all the artists met with the curators to plan the exhibition, I just said that we had this plan and we wanted Studio K. I’m usually a shy person, but there’s a point where you can’t be shy anymore; you have to be a bit firm and say what you want to do. I loved the space even before we were invited to be in this exhibition. I just loved it. It is like a cube, but very high.

S: Like a tower, almost, seen from the inside.

K: For the installation, I wanted to create a nice circus or amusement park kind of feeling with the lightbulbs; inviting the vistor to walk inside this atmosphere. The paintings were square with 2-metre-long sides, but I placed them as rhombuses, so they became even taller, 2.80 metres high. It was the largest size that I could get through the door. I had to screw on all the lamps inside the space itself. If the lamps had been attached before, the paintings would have got stuck in the door.

S: Did you have the idea for the story before you got the space?

K: No. I decided then and there that it would be about happiness.

Narrative painting by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

Narrative painting by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

Narrative painting by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

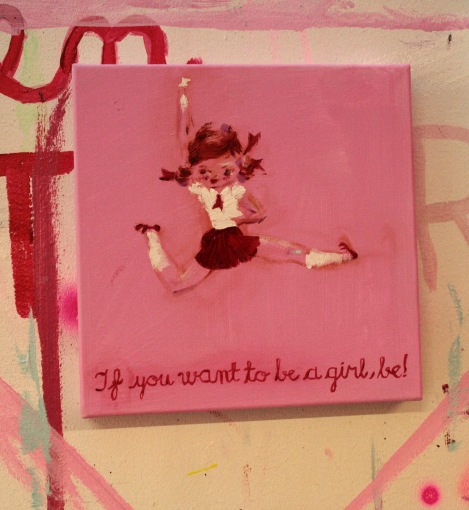

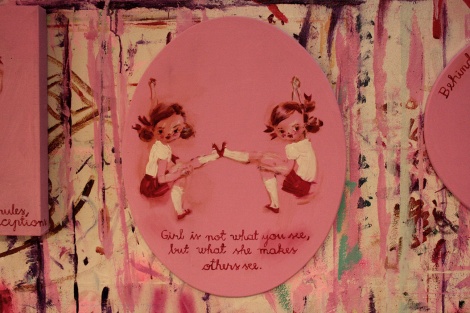

S: One thing that I really like about the story, is that there is this dangerous, gurlesque quality in your girl characters. They are so cute and neat, but at the same time very primal; they act on instinct and they take what they want, they will use brute force if that is needed. On Youtube, there’s a video where you talk about how much you love Pippi Longstocking, who is the strongest girl in the world. So I was thinking about the connections between Pippi Longstocking and your girls, their similarities and differences. Pippi can be very kind, but she will break the rules that doesn’t make sense to her and she always does what she wants. Your girls are like that too, but they move in an entirely different, fluffy and cute universe, full of beautiful animals that they can show love, but also potentially be cruel to. They kind of form a pack as well in this story, which increases my feeling of them being very powerful but with a dangerous side. Can you tell me more about these girls, what are their emotions and desires?

K: I think there is everything. They can be angry, and everything else you would find in humankind. In the story, they take the unicorn as hostage. But there was no danger.

S: I felt danger when I read it, though. It feels like they are going to crucify the unicorn.[laughs]

K: I would never go so far [laughs]. It is good you felt the danger, but in the end the girls are kind-hearted. They can go close to the edge…

S: …but they will not step over it?

K: No.

S: I felt that these girls are moving in the land between; they are really standing on the edge to me. There’s always the suggestion that the situation in the comic could go much further than it does, something violent or out of control could happen. But I really like that, the girlishness that has a darker potential.

K: That’s a nice analysis; that you really felt the danger. I thought, maybe people don’t know how to read this story. You need to know how to read the pictures and the words together.

S: Have people had a hard time understanding your work, because it’s inventive in the sense of combining comics, painting and installation?

K: Maybe, I don’t know. The audience took it well, but I sensed some problems with some people. I don’t know what they felt, but maybe a bit insecure or threatened even… Even though it’s a contemporary art museum. This is something I can’t express so well and I don’t want to blame them, but I just felt that maybe I did something that was too much for them. Maybe people are too shy to ask what the story means? But younger people took it really well.

INSULTED BY THE GIRLISHNESS

S: You have created a large and inviting world of images and characters. I believe that many people can have an immediate, powerful emotion when they see your work, even when they do not know the concept behind it, because it is so visual.

K: But some people, no matter if they are women or men, react negatively to the girly aspects of my work… They take things seriously and can be insulted by the girlishness. Girlishness can be like a slippery slope. It starts off cute but there’s something inside that’s not so much fun, that’s even scary or dangerous. Maybe some people get so slapped in the face by this, that they are like… I don’t know why; but it’s something I’m not able to see myself. I just love the feeling of walking into that kind of atmosphere. It doesn’t have to be art; it could also be an amusement park. You love to see it, but it can be dangerous at the same time, like in Twin Peaks with the red curtains and the black-and-white floors. I want to create that feeling when you go inside this installation. It’s not an intellectual thing; you go inside with your emotions. But then if you read the story, you can start thinking. If you want to; you don’t have to. But for some people… I don’t know. And the museum, even though it’s a contemporary art museum; it’s like a church.

S: When you say it’s a church – does that mean that there are certain rituals and acts that need to be performed there? Do you think you broke the rules of how exhibitions are performed within this museum?

K: Yes, I think so. A professor from the art school commented on the work, saying that I’m making fun of the audience. I would never do that… I don’t understand why some people feel that I’m making fun of them.

S: It’s really interesting that someone can feel that you are laughing at them, just because you ask them to step into a girly world for a while.

K: That’s sad and it’s not my intention. Inside me, there’s a part that can imagine what it is like to be a really strong man and I think in strong men there’s a part that can feel what it’s like to be a woman or a girl, or how it feels to be in a nice, fairy-tale-like atmosphere. They should be able to experience and enjoy these things, we are not so different as human beings. What’s the danger for them?

S: One could say that your work is like an invitation to walk into pink emotions for a moment.

K: For everyone.

S: Pink is really the prominent colour of your work and you use it in so many different ways. Your work include so many possible shades of pink.

K: Both really aggressive and really soft, yes.

S: Do you think people are surprised by this diversity of pink and the emotions of girlhood that you portray in your art?

K: Just recently, this question came to my mind: “Why do I feel that these colours are cute and fairy-tale-like and create this kind of theatrical, immersive atmosphere?” Because there is also… and this is connected to men, mainly. In Helsinki, where we live, there’s a red-light district. Why do these places use red lights? Sometimes they have this kind of pinkish entrance. Is there a connection for some men, between the feelings that they have when they see an entrance like that and when they see my art? I don’t know, but it’s what I thought of recently, this last year.

S: That’s so interesting… It makes me think of some things I learned by reading about sex-worker rights activism, about the widespread hatred in society towards women doing sex work. They can face all kinds of violence, both from the state, from people who dislike sex work and from customers. Maybe the reaction to how you use pink and girlishness somehow is connected to a fear and disgust of women and female power that some men carry around. It’s sort of evoking something in them…

K: It’s something I don’t understand. I live with men, my father, my brother, my son, my husband Matti, my friends… I also have friends who are gay and transgender men. No-one has expressed this to me, or been able to explain it. I mean, I am lucky that I don’t know personally people who have aggressions towards women. Maybe I live in a happy bubble.

Girl mannequin doll showing her tongue, work in progress by Katja Tukiainen. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

K: But I can tell you this memory: many, many years ago, the Finnish book fair commissioned a painting from me for their poster and marketing cards. They wanted a girl showing her tongue, like her [gesturing towards the painting of a girl behind her], but different. A funny, Shirley Temple-like girl. It ended sadly. In the end, I got more money to fix the painting and take the tongue away. They made all the posters and the cards, and I still have some of them in storage, the cards they could never use. Two weeks before the book fair, they called me and said “We are so sorry, and we’re paying you a bit more, so can you Photoshop it so that the tongue is not showing?” I wondered what had happened and tried to get some answers from the lady on the phone. All she revealed was that there was someone, a man, who made the comment that the tongue was not appropriate. I said, “Okay, but can I talk to the man?” It didn’t matter who it was, but I wanted to ask him what he saw in the image. She never gave me the name or the number because she was afraid I would make the situation worse. In a TV show, they showed the original picture and asked what’s the matter; why can’t we have this girl showing her tongue? People asked me, but I couldn’t answer. The book fair people knew why, but they didn’t share it with me. It was of course a man in important position, but nobody knows what he was so threatened by in this image.

M [from his work table]: He saw himself in it.

K: No, but it was telling him something he didn’t want to hear. It was evoking something.

S: It seems like it stirs something in people that is already in them. Something that comes alive or is awakened. I think about now how those feelings and emotions are very instinctive; they are not thought through. This man’s reaction was possibly: “This can’t exist. We have to remove it.” Like it’s too obscene.

K: A bad image.

S: Yes, exactly.

K: That’s scary.

S: And fascinating. There’s a very sexualized view of young girls in society today. I wonder if people feel threatened that your girls, who are prepubescent or in their early teenage years, are not hiding themselves away but instead taking up space and doing whatever they like, that they are not hiding from the gaze of other people.

K: It’s adults who have to know the limits of paedophilia. Those men, they have to know the limits.

S: Do you think that they want the girl to know the limits, instead? Like, this girl should know better than to show her tongue because it makes them feel that something dangerous could happen. So they want to remove her tongue instead of working with their own feelings?

K: It’s so crazy. And in the end, it’s just a painting. It’s not a singer or actor; it’s paint on the canvas.

S: Images are powerful, if they can evoke such a reaction.

K: Really powerful.

S: It also makes me think of this…. Through your installation comics, you allow people to enter into the image in a different way than when they read a comic book. There’s a difference in that you can close a book and put it away; we don’t ever have to look at it again. The ideas are hidden; they are only in the book. But when you make your installation comics, people have to step into the space and be surrounded by the images. It’s like the images becomes a physical world surrounding the reader. The story is larger, and harder to lock away.

K: I love the lock idea. It reminds me of diaries with little locks.

THE YOUNG LADY AND THE UNICORN

Girls and roe deers as characters in Katja’s paintings. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

S: How did you come up with the story in Paradise K Kidnap?

K: First I wanted to comment on the art world, so I thought the girls could kidnap one of the most important curators in the world. But then I thought, “This is art about the art world; it’s not important; there’s nothing for the audience”. So I thought, “What is it that we all need? Happiness”. At least we should all think about happiness. Then came the unicorn who symbolizes the secret of happiness.

S: Why did you choose a unicorn to symbolize this?

K: It’s a very powerful image today in popular culture. But even before that I was fascinated by a tapestry called The Lady and the Unicorn in the Cluny museum in Paris. At the end of the 1990s, I saw a replica of this tapestry in a museum in New York. And even before that, I’d seen it in art history books. When I was young, I wondered what the meaning was behind unicorns and fairy-tale creatures, so I studied symbolism. As an art student, I learned more about the young virginal lady and the unicorn, the hidden tension and electricity between these symbols. Then I wanted to use it in my art for different reasons. These characters have a long tradition in art history and are also very familiar to contemporary audiences through pop culture. Now there’s even an emoji.

S: Young feminist and queer movements use images of unicorns and rainbows a lot in their activism.

K: At the same time, it’s just really nice symbols. I never was a horsey girl since I was allergic, but horses are really important for girls. They are huge, big strong animals that small, tiny girls can handle.

S: But your girls are treating the unicorn very badly in the story! Though, he’s really kind to them, allowing them to do whatever they want to him and he says that he loves them anyway.

K: Because he is so strong, and they can’t really harm him.

S: [laughs] Good to know, because when I read it, I felt that the danger was real. That they could actually do something terrible to him, just out of curiosity. Like, they could do something to him…

K: … just because they want to try it. Oh yes, wow. [laughs]

S: Apart from the unicorns and the girls, you have Bambi, the deer. Can you tell me a bit more about this character?

K: Bambi comes from pop culture and has always been a boy to me. A kind of fragile-looking, cute boy. I just love the character. It’s cute. Unicorns and Bambi are both symbols from my childhood that work really well because they are always going through reincarnations in different media in pop culture, design and fashion. Nobody owns them. In Finnish, we don’t have gendered pronouns so people are often surprised when they hear that Bambi is a boy. If you just read the book, you wouldn’t know his gender.

S: Are the readers expecting a girl?

K: At least some of them, yes. Because he has big eyes.

S: You’ve also painted Bambi with sharp, pointy teeth, like a vampire. Tell me about the teeth.

K: Everything needs an accent. I mean, like a scratch. Nothing can be just one thing, everything has an underside.

.

Katja in her studio. Photo: Saskia Gullstrand

KATJA TUKIAINEN was born in Pori, Finland in 1969. She is a visual artist, working with comics, installations, painting, animation and other media. Her mixed-media installations and site-specific narratives has been shown in exhibitions all around the world, and her books are published in Finnish, Swedish, English and Russian. In 2016, she was the artist in residence at the Museum of Drawings in Laholm, Sweden, creating an exhibition together with her co-artist in residence, Sigga Björg Sigurðardóttir.

Through various media, KatjaTukiainen has created an electrical world of images, full of girls and animals who play, fight and go on adventures. Her army of girl characters are kind-hearted and cute, yet are not harmless. One single desire inspires all her drawings, paintings, installations, sculptures and work. In her own words:

“My need is to lead the audience to the world where cute and small creatures have an opinion and power.”

SASKIA GULLSTRAND is the art director and founder of Underlandet Comics Art Lab. In September 2016, she travelled to the Helsinki Comics Festival to interview the Finnish comic artists Hanneriina Moisseinen, Katja Tukiainen, Hanna-Pirita Lehkonen, Taina Hakala, Johanna Rojola, Tommi Musturi and Amanda Vähämäki. The interviews are part of Underlandet’s ambition to create and share conversations between comic artists.